- Home

- Barbara Linn Probst

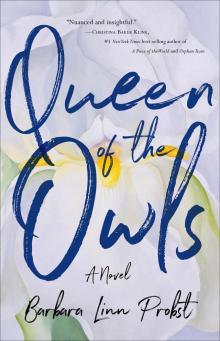

Queen of the Owls Page 10

Queen of the Owls Read online

Page 10

For the second time that day, she thought of Carter Robinson. She had been afraid. Not of Carter or being hurt by him, but of herself. Of finding out who else she might be.

She’d been seventeen. She was twice that age now. The same Liz, because people didn’t change—until they did.

Nine

Andrea rotated the salon chair so they could view Elizabeth’s reflection in the mirror. She ran her fingers through Elizabeth’s hair, fanning it away from her cheeks. “You see how great it looks? I’m so glad you let me do this for you.”

Elizabeth loosened the collar of the nylon cape that Andrea had fastened around her neck. The Velcro was too tight, or else it was anxiety that was squeezing her throat and making it hard to breathe. For years, Andrea had tried to get her to sit in this very chair. “Let me give you highlights and a new cut,” Andrea had begged. “You’d look amazing.”

For years, Elizabeth had refused, and finally Andrea had stopped asking.

Now, she was the one who had asked. “If you’re still willing.”

“Of course I’m willing. I won’t even say told you so.”

Andrea had a small hair salon in the back of her house, light and modern, with bright Mexican tiles and oversized mirrors on two of the walls. Another wall opened into a playroom for the customers’ children. Stephanie, Daniel, and Katie were there now, busily constructing a kingdom out of blocks. Elizabeth could hear their chatter, high and musical, as Spiderman and Polly Pocket chased each other from tower to tower.

Andrea feathered her scissors through the edge of Elizabeth’s hair. “Ben is going to absolutely swoon, but he won’t be able to figure out what’s different.”

“Ben doesn’t swoon.” Andrea knew that. She had told her, the night they had pizza.

“He will now.” Andrea twirled the chair and pulled off the nylon cape. Then she stepped back and regarded Elizabeth with a satisfied grin. “You really should have done this ages ago, Lizzie. That sixties look didn’t do a thing for you. All it did was hide your beauty.”

Elizabeth met her sister’s eyes, touched by the generosity in her words. “Who knew you could be so sweet? I might have to report you to the sibling rivalry patrol.” Then her expression turned grave. “You don’t think it’s weird, me doing something like this?”

“Why would it be weird?”

“Because.”

“Because you’ve always been Miss Bookworm?”

Elizabeth winced. “I guess.”

“It doesn’t mean you can’t look good. Anyway—trust me on this, Lizzie—just doing this will put you in a different frame of mind. Feeling gorgeous and sexy is the best way to make a man see you as gorgeous and sexy. And Ben will, I guarantee.”

Why did Andrea keep talking about Ben? As if a haircut—or a negligee—would make a difference. You didn’t change a relationship by putting on a costume. They’d proven that already. Anyway, she wasn’t doing this for Ben.

Richard’s face rose up in front of her, the smoky grey of his eyes, the carved plane of his cheeks. She felt the touch of his hand on her spine as he led her to a table in the back of the café, the firmer touch as he pushed her forward on the swing. Her gaze darted to Andrea, but Andrea had turned to wash her hands in the sink.

New little tricks in bed.

“Andie,” she began. She needed to talk about Richard. Despite their differences—because of their differences—Andrea might actually understand.

Shouts rang out from the playroom, and Stephanie came running into the salon. “Mommy, Mommy, look!” She held out a plastic Superman. The figure was wearing a frilly pink dress over its molded blue tights.

Daniel ran after her. “Give it back, fart head.” He grabbed the toy.

“Stop it, both of you,” Elizabeth said.

“Oh, let old Superman try some cross-dressing,” Andrea laughed. “Might do him some good.”

“It’s not funny.” Elizabeth’s voice was sharp. “It’s about taking other people’s toys.” She took the action figure from Stephanie and dropped it in her lap. “Superman is in time-out. Go find something else to play with. Both of you.” She shooed them back to the playroom.

“Whoa,” Andrea said. “You’re pretty uptight, especially for someone who just had my best salon treatment.” When Elizabeth didn’t answer, she reached for a towel. “I thought you had this big plan to get all blissed out. Didn’t you sign up for some kind of yoga class?”

“Tai Chi.”

“Whatever.” Andrea wiped her hands. “So, is it working? Making you all mellow and relaxed?”

Elizabeth picked up the Superman figure. “I don’t know yet.” She traced the line of the red cape, moved the plastic arms up and down. “I’ll have to see what happens.”

“I suppose it takes a while.”

“Hard to say.” Again, Elizabeth longed to give words to the feeling that was pushing through her skin, clamoring to be named. Her fingertips grazed Superman’s face. The handsome features were fused into place.

No, she thought. She couldn’t talk about it. Not yet.

Andrea took off her smock and hung it on a hook. “Well, that’s it for this morning. I have a keratin after lunch.”

Elizabeth swiveled her chair to survey the salon. Two big mirrors, a hair dryer and sink, a tall cabinet made of plastic boxes. “You could do so much more with this, you know. Really make it into something.”

“I like my little shop.”

“Seriously,” Elizabeth went on, the notion seizing her. She could help Andrea, give her a return gift. It was only right. “Some business courses, Andie, that’s what you need. You could learn how to market yourself, create your own brand.”

“Eh. Not my thing. I hate school and school hates me.” Andrea lifted her hair, twisting it into a knot. “It’s the hair part I like. I don’t need business classes to do hair.” She dropped her hands, and the tresses fell to her shoulders.

“But you could. Really. A lot of people get business degrees.”

“Stop it, Lizzie.”

“I mean it. You’re smart enough.”

“I’m not, and I don’t need to be.”

“But—”

“I said stop. Strange as it may seem to you with all your fancy degrees, I’m happy doing hair.”

“Okay, okay.” Still, Elizabeth thought, how could doing hair possibly be enough? Of course, Andrea could volley back the opposite challenge. How could sitting in libraries, writing papers, be enough? Well, it was enough for Marion Mackenzie. And she was like Marion— or would be, soon, if she worked hard and her luck held.

She hadn’t replied to Marion’s invitation, not yet. Marion’s secretary had emailed with the location of the gathering and a request to confirm her attendance. Elizabeth told herself that the choice was obvious; she’d be crazy not to go. She started to tap reply a half-dozen times, ready to accept the invitation.

Of course, the talk was about Arthur Dove, not Georgia O’Keeffe. It wasn’t as if she had been given a one-time-only chance to look at secret O’Keeffe papers. The point was that Mackenzie had offered a relationship. Mackenzie understood about child care; she wouldn’t hold it against her if this particular Wednesday didn’t work out.

Elizabeth’s mind spiraled from Dove to Stieglitz, because Dove was part of Stieglitz’s inner circle. Stieglitz had written to Dove: “When I make a photograph, I make love.”

Andrea’s words cut into her reverie. “And I’m good at doing hair.” She gave the chair a playful spin. “Let me know if my masterpiece lights Ben’s fire.”

Elizabeth braced her feet on the rubber mat, halting the chair in mid-spin. “Andie.”

“You act like you don’t want to light his fire.”

“It’s complicated.”

“Why is it complicated?”

Elizabeth closed her eyes.

Because I’m not sure he wants his fire lit, or if I can light it. There might be other fires.

“Mama.” It was Katie this time, tired

of trying to keep up with Daniel and Stephanie. Elizabeth opened her eyes, and then her arms, as Katie climbed onto her lap. “Mama,” she sighed, burrowing against her.

Elizabeth pressed her cheek to her daughter’s hair. “Tired, sweetie?” She expected Katie to deny it as she usually did, but Katie nodded. “You rest, then,” she told her. “It’s all right.”

Andrea locked eyes with her in the mirror, her shrewd look letting Elizabeth know that she hadn’t answered the question.

On Wednesday, as Marion Mackenzie’s lecture was beginning in another part of town, Richard guided Elizabeth into the coffee shop where they had shared an Americano two weeks before. She’d imagined going back to the playground but it was raining, a cold grey drizzle. Anyway, the café had reopened.

She had emailed Marion Mackenzie’s secretary to say that her sitter had come down with the flu. She hadn’t mentioned the invitation to Ben. He hadn’t even noticed her new hairstyle, so he had no claim—that was what Elizabeth told herself—on her decisions. She left a chicken casserole for dinner and hurried to the fourth-floor studio.

Richard led the pupils through the sequence of movements. “Mr. Wu is happy that we’ve been meeting,” he told them.

To Elizabeth, his words were a code, a message just for her. Richard ended the practice early, and she waited for him by the entrance on the ground floor.

He greeted her with a delighted smile, his palms open wide. “Your hair looks wonderful.” Then he motioned to the street. “I believe you owe me a cup of coffee.”

“I do.”

Richard tilted his head, studying her. Then he said, “Come. I discovered an interesting fact about your Mr. Stieglitz. I’ll tell you while we have coffee.”

As if Elizabeth needed something to entice her, besides Richard himself. But she nodded, pretending to agree to his terms, and waited till they were seated to ask, “So. What is it you discovered about Mr. Stieglitz?”

Richard signaled to the waiter, mouthing the words two Americanos. Then he leaned closer, planting his elbows on the marble. “You know how he was photographing O’Keeffe in the 1920s, right?”

“Of course.”

“Well, people might think O’Keeffe was the only subject he was interested in, but she wasn’t. So I checked out a hunch.” He lowered his chin, teasing her. “You’re supposed to ask me about my hunch.”

Elizabeth flushed. “Tell me about your hunch.”

“1922,” he said, “the year Stieglitz started to take pictures of clouds. He wanted to photograph clouds to find out what he actually understood about photography. He said the cloud photographs were the equivalent of his most profound life experiences, a visual image of his philosophy of life. That’s what he called the series, Equivalents, these amazing photos he took between 1925 and 1934.”

“All right. And your hunch?”

Richard’s face turned serious. “That he was photographing Georgia through the clouds, and the clouds through Georgia. To him, she was everywhere.”

Elizabeth grew quiet, strangely moved by what he had said. “Yes, I think so too.”

The waiter appeared with their coffee. Elizabeth drew back to give him room.

The corner of Richard’s mouth twitched as he reached for his cup. He was teasing her again, Elizabeth thought.

“On the other hand,” Richard went on, “it seems that my revered Edward Weston was a bit of a copycat. He met Stieglitz for the first time in 1922, and went on to photograph—you guessed it. Clouds. Other things too. But if you look at his cloud photos, the debt to Stieglitz is hard to miss.”

Elizabeth felt the heat of her coffee cup, its curved shape between her palms. She longed to tell him what she had discovered about Weston’s nudes, the way the women in Weston’s photos were either faces or bodies. It was a pattern that anyone who really looked at the pictures might notice. Yet she hesitated, because it was more than that. If she told Richard what she’d seen, it would be like telling him about herself.

She edged forward, closing the space she had ceded to the waiter, and met his eyes, those grey ovals rimmed with charcoal. The smell of freshly ground coffee filled the café, wrapping her in a thick aromatic haze.

Then Richard spoke again. “I think O’Keeffe’s paintings inspired Stieglitz’s cloud photos. And I think modeling for him inspired her, in her own work.”

Elizabeth inhaled, drawing the scent of the coffee into her lungs. “Yes, I think so too. Her work absolutely exploded after she started posing. Those flower paintings? They were all from the 1920s. She hadn’t done anything like that before. She wasn’t able to, until she’d modeled for him.”

“Maybe posing freed her,” Richard said. “Or maybe it was Stieglitz’s passion.”

Elizabeth felt herself redden. She caught her breath. “You mean, as a photographer? He photographed her endlessly, you know, once she came to New York.”

“Weren’t they lovers?”

“Not at first.”

Richard eyed her intently. Flustered, Elizabeth kept talking. “It was part of how their relationship was changing. He started by photographing her hands and face, these amazing close-ups. After a while they did become lovers, and the portraits changed too. There’s this quote from one of O’Keeffe’s letters about how he began to photograph her with a new heat and excitement.” Her flush deepened. “Those were her words. It was quite mutual, apparently. A mutual intoxication.”

Richard raised his coffee cup. “Mutual intoxication makes for great art.”

Elizabeth watched his throat as he drank. She thought of Stieglitz, learning Georgia’s body through his camera. Deliberately, with a fire that ignited them both.

When I make a photograph, I make love.

Then Richard set the cup on the table. “So. I’ll repeat my question. How are you going to actually understand O’Keeffe?”

By doing research. Obviously. That was how you got a PhD.

“Not by writing about her paintings,” he said. “You know that.”

Elizabeth tried to keep her tone light. “Oh? And what do you suggest?”

“You have to do what she did.”

“Hardly. I’m not artistic. I can’t paint to save my life.”

“That’s not what I’m talking about.”

His gaze bored into her like a laser. She wanted to say, “Then what are you talking about?” But she knew. She had known from the first time they had coffee together.

The noise in the café receded. The swirl of people, the clang of the espresso machine, the coldness of the marble against her skin— everything drew back, grew silent.

She had to reveal herself. Be seen.

The very thing she wanted, and the very thing she feared.

Images of Georgia tumbled across her brain. A woman in a white skirt, looking up from her work. The same woman in an open robe, drowsy and disheveled.

The air in the coffee shop was thick as a mattress, pressing against her from all sides. Elizabeth brushed back her hair, the glinting highlights and flattering haircut that Ben hadn’t noticed but Richard had. She felt her hair against her neck. Imagined that neck bare. Imagined her whole body, bared to him.

She made herself ask. “What are you talking about, then?”

His expression was sharp and clean, like the edge of a blade. “You have to know in your whole self and not just your mind.”

Her whole self. All her body parts, favorite and un-favorite.

She yearned to give words to what he was offering. A portal to another way of knowing, when nothing separated you from the thing known.

Say it for me.

As if he had read her thoughts, he told her, “You have to do what O’Keeffe did.”

“You mean, pose?” Her voice cracked.

“I mean pose.”

“For you.”

“For yourself. I’d just be the one holding the camera.”

She thought of the long hours Georgia had given over to posing— letting Stieglitz arrange her body the

way he wanted, holding each position for minutes at a time. If Stieglitz was creating his art, Georgia couldn’t create hers. And yet, by giving him her time and her body, she found her own beauty. Out of that, her art changed. In being seen, she saw.

Elizabeth felt the staccato of her heartbeat, pushing against its cage. The notion of posing, as Georgia had, was outrageous. No one who knew her would believe she’d consider such a thing—and yet she had already crossed a line, just by having this conversation. “Why are you doing this?” she asked. “You hardly know me.”

Richard shrugged. “I’m a photographer. You’ve got me intrigued. You and your Georgia O’Keeffe.”

That’s right, it was about Georgia. Elizabeth’s mind shot ahead, grabbing at words like handholds. Of course. An artistic inquiry, a joint experiment. A different kind of research, with a photographer as her guide. That’s what they were talking about.

No, this was insane. She was an academic. A wife and mother. Not a person who took off her clothes for strangers.

Besides, no one really knew why Georgia had posed. It might have been private, part of their love-making, or a way to support her lover’s artistic growth. Or maybe not. There were people who claimed that the photos were a deliberate image construction, to get her talked about. And it had worked. After Stieglitz exhibited his portraits of her, her own paintings started to sell.

Elizabeth’s head spun. If she didn’t know why Georgia had posed, how could she imitate her? It made no sense. Then again, Richard had said that posing was the way to understand O’Keeffe. If she posed, she would understand. That was the order.

For Georgia, the gradual revelation, through posing, had been a kind of foreplay. She’d been a virgin, after all.

Elizabeth shivered. She was jumping to conclusions. Stieglitz had photographed O’Keeffe in a whole spectrum of postures and moods. Austere, androgynous, in a mannish suit or a black cape. Why was she assuming that Richard meant the nude poses?

Queen of the Owls

Queen of the Owls