- Home

- Barbara Linn Probst

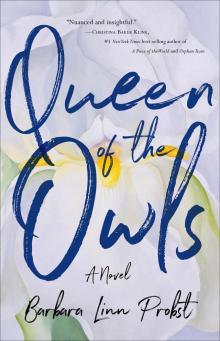

Queen of the Owls

Queen of the Owls Read online

Praise for Queen of the Owls

“A nuanced, insightful, culturally relevant investigation of one woman’s personal and artistic awakening, Queen of the Owls limns the distance between artist and muse, creator and critic, concealment and exposure, exploring no less than the meaning and the nature of art.”

—Christina Baker Kline, #1 New York Times bestselling author of A Piece of the World and Orphan Train

“This is a stunner about the true cost of creativity, and about what it means to be really seen. Gorgeously written and so, so smart (and how can you resist any novel that has Georgia O’Keeffe in it?), Probst’s novel is a work of art in itself.”

—Caroline Leavitt, best-selling author of Pictures of You, Is This Tomorrow and Cruel Beautiful World

“Queen of the Owls is a powerful novel about a woman’s relation to her body, diving into contemporary controversies about privacy and consent. A ‘must-read’ for fans of Georgia O’Keeffe and any woman who struggles to find her true self hidden under the roles of sister, mother, wife, and colleague.”

—Barbara Claypole White, best-selling author of The Perfect Son and The Promise Between Us

“Probst’s well-written and engaging debut asks a question every woman can relate to: what would you risk to be truly seen and understood? The lush descriptions of O’Keeffe’s work and life enhance the story, and help frame the enduring feminist issues at its center.”

—Sonja Yoerg, best-selling author of True Places

“Readers will root for Elizabeth—and wince in amusement at her pratfalls— as she strikes out in improbable new directions … An entertaining, psychologically rich story of a sometimes giddy, sometimes painful awakening.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“A gifted storyteller, Barbara Linn Probst writes with precision, empathy, intelligence, and a deep understanding of the psychology of a woman’s search for self.”

—Sandra Scofield, National Book Award finalist and author of The Last Draft and Swim: Stories of the Sixties

“Barbara Linn Probst captures the art of being a woman beautifully. Queen of the Owls is a powerful and liberating novel of self-discovery using Georgia O’Keeffe’s life, art, and relationships as a guide.”

—Ann Garvin, best-selling author of I Like You Just Fine When You’re Not Around

“A beautiful contemporary novel full of timeless themes, elegantly portraying one woman’s courage to passionately follow the inspiration of Georgia O’Keeffe and brave the risk of coming into her own.”

—Claire Fullerton, author of Mourning Dove

“Obsession, naivety, seduction, desire, self-deception, love, and courage—all emotions subtly and powerfully revealed in this story of Elizabeth, mother, wife, and intellectual, as she follows her idol, artist Georgia O’Keeffe, along a path to herself. A thought-provoking novel that readers will want to savor and share.”

—Jenni Ogden, author of Nautilus Gold and multiple award-winning A Drop in the Ocean

QUEEN OF THE OWLS will be the May 2020 selection for the Pulpwood Queens, a network of more than 800 book clubs nationwide. In the words of founder and CEO, Kathy L. Murphy: “An absolutely wonderful book that every woman should read!”

Queen of the Owls

Copyright © 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, digital scanning, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, please address She Writes Press.

Published 2020

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN: 978-1-63152-890-3 pbk

ISBN: 978-1-63152-891-0 ebk

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019911275

For information, address:

She Writes Press

1569 Solano Ave #546

Berkeley, CA 94707

She Writes Press is a division of SparkPoint Studio, LLC.

All company and/or product names may be trade names, logos, trademarks, and/or registered trademarks and are the property of their respective owners.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Cover image: White Iris No. 7 (1957) by Georgia O’Keeffe

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain.

For the roses

had the look of flowers that are looked at,

accepted and accepting.

T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets

Part One:

The Photographer

One

Everyone had to meet somewhere. If Elizabeth thought about it that way, the fact that she met Richard at a Tai Chi class was no more or less auspicious than a first meeting at—say, a book store or bus stop. It was only later, looking back, that everything seemed heavy with meaning.

She had seen people practicing Tai Chi on Founders’ Lawn in the center of campus—the unbelievably slow flexing of an arm or foot, the serene gaze that always made her feel, in contrast, nervous and clumsy. She had watched, entranced, as they rotated their hips and pushed effortlessly against the air. After a while, it felt odd to simply watch. Being inside the movements instead of looking at them, that was the point.

The Tai Chi studio was only a few blocks from the university and offered a discount to faculty and students. Elizabeth was both, a PhD student who taught undergraduate courses, which she took as a double sign that she ought to enroll. Besides, Ben had his squash games two evenings a week. It was only fair for her to have Wednesdays. Ben could manage. He knew how to read Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel at least as well as she did—better, according to Daniel. At four-and-a-half, Daniel was quite sure of his judgments.

Ben wouldn’t begrudge her one night a week. And then, when she came home, tranquil and balletic, he’d applaud her decision. Anyway, that was the theory.

The classes were held in a converted factory, in the fourth-floor studio of a short, grave martial arts instructor with limited English. Elizabeth tried to explain that Tai Chi was new to her, but he cut her off. “You can,” he said. “You try, and you can.”

Really? Elizabeth wanted to say. Tell me one thing in life that works that way. But she nodded with what she hoped was the right combination of humility and confidence. Then she took a place in the back of the room where she could steal glances at the other pupils. Most of them, she saw, had been doing this for a long time. It was clear from the elegant, almost bored way they twisted and stretched.

She noticed Richard the moment he came in. It was hard not to, the way he strode into the dojo and placed himself right in the center of the front row, his gaze fixed on the instructor, steady as steel, as if demanding that the instructor focus on him too. Mr. Wu—that was the instructor’s name, although people called him sifu, or master— gave a short bow, acknowledging that the class could begin, now that the person who mattered was there.

“Hey, Richard,” a woman called. She gave a bright, eager wave.

Mr. Wu frowned. Then he placed his left foot parallel to the right and said, “We commence.” Elizabeth tried to concentrate on imitating each of Mr. Wu’s gestures, but her eyes kept straying to Richard. He was the best one in the class; that was obvious. And he was absurdly handsome. Or maybe, she thought, he just acted as if he were.

By the third Wednesday, she found herself watching for him, tracking his movements as he stepped out of the freigh

t elevator and tucked his shoes into a cubbyhole. Adolescent, she told herself, but what was the harm? She had seven days and six evenings a week to be mature, serious, married.

On the fourth Wednesday, twenty minutes into the class, Mr. Wu grabbed his chest and sank to his knees just as they were doing The White Crane Spreads its Wings. Even the grabbing and sinking were fluid, composed. Elizabeth thought, at first, that they were a special part of the sequence. I submit to the source of existence. I accept the impermanence of the body. When she realized what was happening, she stared in horror. Mr. Wu’s face turned ashen as his eyes rolled back in his head and he crumpled onto the hardwood floor. Two of the women screamed.

Richard sprang into action. He jumped forward and caught the old man before his head hit the floor. “Someone call 911.” Elizabeth fumbled in her pocket. You were supposed to leave your cell phone in a cubbyhole, along with other non-Tai Chi-like items, but she’d stuffed hers into the pocket of her cargo pants. She hadn’t meant to be subversive; it was only the habit, since she became a mother, of keeping her phone nearby.

“Here,” she said. “I’ve got a phone.” She pushed through the rows. Richard’s arm was around Mr. Wu’s shoulders, his palm cupping the back of the teacher’s head. He looked up at Elizabeth. His gaze bore right into her, searing her with its intensity. She felt herself turn weak with shock. Was she going to collapse too? Only it would be from the most extraordinary swell of desire, as if someone had turned her upside-down and shaken her like a kaleidoscope, rearranging all the parts.

“Can you call?” he asked.

She blinked. “Yes, of course.”

A man with a shaved head rushed forward. “Check his airways.” He flung a glance at Elizabeth. “I was a lifeguard, back in high school.” Richard moved aside to let the man kneel next to him, and Elizabeth punched 911 into her phone. She told the dispatcher what had happened.

“Well?” Richard looked at her again.

She shoved the phone back into her pocket and buttoned the flap. “They’re on their way.” She inched closer, her knee brushing Richard’s shoulder as he and the other man laid Mr. Wu on his side. She was one of the rescue squad now, a member of the intimate circle.

Within minutes, the paramedics burst out of the freight elevator, carrying a gurney. No one knew where Mr. Wu’s insurance card was, or his driver’s license. A woman in blue yoga pants gave the paramedic one of the postcards for the dojo that littered the top of the shoe cabinet. “It has his name and phone number,” she explained.

The man with the shaved head stepped in front of her and put up a hand, as if he were halting traffic. “I think he has a daughter nearby. If you need a relative.”

The EMT pocketed the card and bent to hoist the gurney. As quickly as they had come, the crew disappeared. Elizabeth watched the lights above the freight elevator until they stopped at the ground floor. With Mr. Wu gone, the studio seemed empty, pointless. She wondered if he would be all right. The possibility that he might not be, and that there might not be more classes, filled her with dismay. Was this it, then? Her Wednesdays, over already?

The students began to collect their belongings. “I’ll be the last to leave,” Richard volunteered. “Someone should make sure the place is locked up.”

“What do you think will happen?” Elizabeth asked.

He shrugged. “No way to know.” He met her eyes again. It was the same look, piercing her like a javelin. “Guess I’ll come by next week and see if anyone’s around with information.”

“Me too,” Elizabeth said. “I’ll stop by too.” The eagerness in her voice, audible even to her, made her flush. She cleared her throat. “I hope he’s okay.”

The woman in the yoga pants put her palm on Elizabeth’s arm. “I’m going to visualize him radiating wellness. I think we should all do that.”

One by one, the students gathered around the elevator. Reluctantly, Elizabeth joined them. It was too early to go home. She wanted to turn around and offer to help Richard lock up, or maybe invite him for a drink. Both ideas were crazy—everyone would stare at her if she threw herself at him so outrageously. The sensation of Mr. Wu’s absence washed over her anew. One minute you were doing The White Crane Spreads its Wings, and the next minute your life might be over.

The elevator arrived and Elizabeth got in. It took forever to descend the four flights to the street. When she stepped out of the building, she looked around for the ambulance but it was gone. There was only a wire trash basket by the curb with a newspaper caught in the mesh and a blur of tire tracks. Elizabeth buried her hands in her pockets and started to walk. The evening was clear and starry, strangely warm, even though summer was long past. The bus stop was only a block away. Without really deciding to, she kept walking. It was twenty-two blocks to the apartment, and by the time she got home, Daniel and Katie would be asleep. She loved them—beyond measure—but the reality of their dense demanding bodies, their overwhelming and exuberant love, was more than she could bear right then.

When she opened the front door, she saw that Ben was engrossed in a Vietnam documentary. He glanced in her direction, raising his chin in a quick acknowledgement before turning back to the screen. His response to her return shouldn’t have been surprising and yet it was. Elizabeth didn’t know what else she’d expected. A leap to his feet, an exclamation of delight, a passionate embrace? Ben never greeted her like that; why would he do that now, on an ordinary Wednesday? It was only the memory of Mr. Wu crumpling, and her knee against Richard’s shoulder, and the smoldering way Richard had looked at her, that made her yearn, suddenly, for a wordless something whose absence she’d grown used to.

Blinking back her disappointment, Elizabeth bent to pick up Katie’s bunny where she must have dropped it on the way to bed. Had Katie really fallen asleep without Mr. Bunny? She glanced at Ben again, her fingertips stroking the bunny’s ear, waiting, in case he decided to look up and speak to her. The thwack of helicopter blades and the rumbling of the narrator’s voice filled the room. Ben’s eyes were fixed on the screen. After a moment Elizabeth gathered the bunny, a pair of inside-out socks, and Katie’s lime green sweater, and elbowed open the door to the children’s bedroom.

The larger of the apartment’s two bedrooms, the room had been partitioned into two rectangles. On one side of the partition, Daniel snored peacefully, legs flung across the Buzz Lightyear blanket that he had kicked aside, an arm dangling off the edge of the bed. On the other side of the partition, Katie lay curled in a ball, fists beneath her chin, knees pulled to her chest. Elizabeth bent and tucked the bunny next to her cheek. Katie frowned in her sleep but Elizabeth knew she’d be happy when she awoke and found the familiar comfort of its matted fur. She smoothed the blanket and kissed the top of her daughter’s head.

Elizabeth closed the door softly and crossed the living room, careful not to walk between Ben and the screen, and went to the alcove where she had her desk. With the Tai Chi class out early and the children asleep, she could get some work done.

She was a doctoral student in Art History, writing her thesis on Georgia O’Keeffe’s time in Hawaii. It was an interlude that most biographers and art historians tended to dismiss, and most fans of O’Keeffe’s paintings had never heard of. O’Keeffe was known for her mesas and deserts, her bones and skulls—and, of course, those flowers. Yet O’Keeffe had spent nine weeks in Hawaii at a crucial time in her life, painting lush green waterfalls, exotic flora, and black lava. They weren’t her best paintings but without them she might not have gone on. They had gotten her past a time of stagnation—a stalled career, a marriage in serious trouble—and prepared her for what would come next. Her transitional place. That was Elizabeth’s argument.

She opened her laptop and pulled up her file of O’Keeffe quotations. The one she needed was right there, at the top of the document. I’ve been absolutely terrified every moment of my life and I’ve never let it keep me from doing a single thing I wanted to do.

Then she reached for

her folder of O’Keeffe’s Hawaii paintings and took out the four images of the luxuriant ’Iao Valley. It was the only large-scale vista that Georgia had painted while she was there, and the only Hawaiian subject she had painted multiple times. Three paintings were of the same waterfall, a jagged line cutting into the verdant slope. The first two versions were bounded, complete, a static landscape, captured at an instant in time. It was only in the third painting that she had let the valley open and pour forth, steam rising from the vortex. Or perhaps it was the fog that was entering, filling the cleft.

Elizabeth felt a stab of desire, a longing for something wide and nameless. Slowly, she slid her finger along the line in the painting where the mist parted and sliced the grey. Then she shivered, as if her own breastbone had been sliced open, expanding, like a pair of wings.

Two

Elizabeth reached across Ben’s chest to turn off the alarm. He lifted his head from the pillow, grunted, and said, “Don’t tell me it’s 6:30 already.”

“6:24. I set the snooze button.”

He let out a groan and rolled onto his side. “You want the first shower?”

“I do. Thanks. I have to get the kids to Lucy’s earlier than usual.”

Ben pulled the edge of the blanket over his shoulders, and Elizabeth’s arm slid off his chest onto the mattress. Her nightshirt was still bunched around her waist. The irritating twist of the fabric and the stickiness between her legs let her know they’d had sex during the night. Not that she had slept through it. Only that it had been, as usual, unmemorable.

She rolled onto her back, allowing herself those six extra minutes before she really did have to get up, and moved her legs under the sheet, scissor-like, until she felt Ben’s calf against her toe. He twitched, jerking toward the edge of the bed. Elizabeth reached down to straighten her nightshirt.

Obviously she knew they’d had sex, the same way she knew that the rent was due or that she needed to move a load of laundry from the washer to the dryer. She’d been nudged half-awake by Ben’s erection against her butt. Her first thought had been: Thank goodness. It had been a while. It was always a while, although Elizabeth had trained herself not to watch the calendar too closely because that made it worse. Still, an actual erection—even if it came from a particular sleep position and not from touching or seeing or anything to do, specifically, with her—was too precious to waste. She had shifted her weight carefully, nothing sudden that might startle him into limpness, and guided him toward her.

Queen of the Owls

Queen of the Owls