- Home

- Barbara Linn Probst

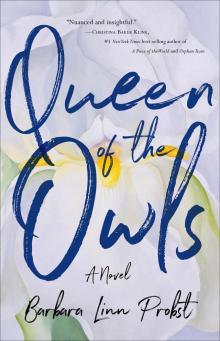

Queen of the Owls Page 2

Queen of the Owls Read online

Page 2

Not memorable, but duly accomplished.

Elizabeth heard the click of the alarm that meant it was about to buzz again. Quickly, she leaned across the bed to shut it off so Ben could sleep a little longer. She had a packed day but his would be tougher. Ben was a lawyer, though not the kind of lawyer with glamorous high-paying cases. Some of his clients didn’t pay at all. Partner in a small local firm, Ben took on working-class clients who needed help with leases and disability claims and an occasional bequest. He was dedicated, conscientious, and saw each flat-fee case through to the end, regardless of how long it took. That included a string of tenants’ rights lawsuits that were seldom winnable but, he insisted, important to the community. Elizabeth admired him for that.

“Wake me when you’re done with your shower,” he mumbled.

“Will do. I’ll turn on the coffee maker while the water heats up.”

Elizabeth folded back the blanket and eased off the bed. Ben liked to take a cup of coffee into the bathroom while he shaved. It was one of the things she knew about him, just as he knew that she liked the toilet paper to unroll from the back and not over the top. If there were other things he didn’t know about her—well, she was too busy to dwell on what she didn’t have.

Her priority right now was to get showered and dressed so she could turn her attention to Daniel and Katie. She had an 8:30 meeting with her dissertation adviser, who clearly had no idea what it took to get to his office at that hour. An 8:30 meeting meant that Daniel and Katie had to be settled at the babysitter’s by 8:00, and that meant waking them by 7:00. They didn’t mind going to Lucy’s house. Lucy had a big yard, an endless assortment of toys, and other preschoolers to play with. It was the getting-up and getting-there that was so challenging.

Elizabeth did the seven-minute wash-and-towel-dry she had perfected after Daniel was born, slipped into her clothes, and stopped in the kitchen to pour Ben a cup of coffee. She set the cup on the bathroom sink, tucking it under the protective edge of the medicine cabinet. Ben was already in the shower. Steam billowed into the room, like the cloud that had filled the cleft of the ’Iao Valley. Elizabeth wiped a circle on the shower door and yelled, “Bye! See you tonight.” Then she hurried down the hall to the children’s bedroom.

“C’mon, pumpkin,” she told Katie, lifting her out of bed. “Up you go.” Katie rubbed her eyes and started to protest, but Elizabeth scooped up the bunny and jiggled it up and down. “Good morning,” she squeaked in Mr. Bunny’s distinctive soprano. “What color socks do you want to wear today, Miss Katie-Kate?”

Katie wriggled free. “Pur-pill.”

“Excellent.” Mr. Bunny bobbed his head.

From the other side of the partition, Elizabeth heard Daniel slide out of bed and pad across the floor. “Are we going to Lucy’s?”

“We are indeed.”

“Knew it.”

Elizabeth had to smile at the smack of satisfaction in Daniel’s voice. How nice to have the world verify, so clearly, that you were right. She opened Katie’s drawer and found a pair of lavender socks. “What do you think, Tiger?” She raised her voice so Daniel could hear. “Gonna beat the world championship record for getting dressed this morning?”

“Yes!” She heard the bang of his bureau and wondered, briefly, what he was pulling out to wear. Oh, let him pick; he liked that. She unrolled the socks and reached for Katie’s foot.

“Me,” Katie said, pushing her hand away.

“Can Mr. Bunny help?” Katie shook her head, as Elizabeth had known she would. She separated the purple socks and dangled one from each hand. “Which shall we do first?”

Katie grabbed a sock and stretched it over three toes, face scrunched in concentration. She tugged, and her big toe popped free. Elizabeth could see the purple nylon beginning to tear. If that happened and Katie had a tantrum, they’d never get to Lucy’s on time.

Enough. She picked up Katie’s foot and snapped the sock into place. Katie opened her mouth to object, but Elizabeth threw her a don’t you dare look and picked up the other sock. “Here you go. Purple sock number two.” Then she plucked a flowered shirt from the drawer. “Up, please.” Katie raised her arms. “That’s my girl. Want to pull it down yourself?”

Without turning her head, Elizabeth called out to Daniel. “How’s it going, Tiger? You ready, or do you need some help?”

“No,” Daniel said. Elizabeth didn’t know if it meant no, he wasn’t ready, or no, he didn’t need any help. She looked at her watch. 7:20. No time for breakfast. She couldn’t let her children go to Lucy’s without breakfast, but she couldn’t be late for her meeting either. Getting Harold Lindstrom to chair her dissertation committee was a coup and not to be taken lightly. Lindstrom was a stickler for footnotes, MLA citations, and promptness.

“I know,” she announced. She shook out a pair of overalls and made her voice as bright as she could. “Let’s get Egg McMuffins on the way to Lucy’s.”

Ben would never start the children’s day with Egg McMuffins. Of course, Ben wasn’t the one in a rush to get them to daycare. Elizabeth remembered the lifted nightshirt and the way he’d jerked his leg away when she touched it with her toe. He was half asleep, she reminded herself. It was a reflex, not a rejection. Then she thought of his averted profile and absent nod when she came back from Tai Chi last night. Nothing unusual about the greeting, yet it had stung. The barrenness of their exchange—no kiss, no smile of pleasure at her return, not even a brief muting of the Vietnam documentary to ask so how was Tai Chi?

And what would she have answered? The teacher opened his arms and fell to the ground. A man looked at me.

If she’d wanted to talk about the Vietnam War, Ben would have made room for her on the couch. On another night, she might have done that; they’d had plenty of similar conversations over the years. It was what they did, analyzing and dissecting and figuring things out. The changing composition of the Supreme Court, the bioethics of stem cell research. Agreeing, in principle, about the way life should be.

Elizabeth pulled her lips together with a firm no to wherever her thoughts were taking her. It was after 7:30. Hastily, she collected sweaters, car keys, bag, and bunny.

Somehow she got the children into the car and settled at Lucy’s by 8:03. Then she raced to campus, took the stairs in the Humanities building two at a time, and knocked on the pebbled glass door to Harold Lindstrom’s office at 8:29.

As she had feared, Harold Lindstrom wasn’t happy with the outline she had sent him. “You haven’t convinced me,” he said, eyeing her over the rim of his tortoise-shell glasses. “The whole point of a dissertation is to make a new argument, based on the evidence. Without evidence, it’s wishful thinking, not scholarship. Opinion masquerading as critical interpretation.”

“Yes, of course.” Elizabeth tried to look grateful for the platitude without ceding her confidence. The combination of humility and assurance she’d aimed for with Mr. Wu was also, as she had learned, the proper stance for a doctoral student. “In fact,” she said, “my idea is rooted in O’Keeffe’s whole approach to art. She wanted to show the essence of things.”

“Indeed,” Harold said. He sat back, folding his arms. “But why, specifically, did Hawaii matter?” He gave Elizabeth a dry look. “Let’s be honest. The stuff she did in Hawaii wasn’t all that good.”

“That’s not the point.” Elizabeth took a deep breath. Harold Lindstrom liked her, thought she had exceptional promise; that was why he’d taken her on. She was determined to be his prize student, write the most ground-breaking dissertation he had ever seen, and in record time. But first she had to make him understand her idea—no, more than understand. Admire it.

“It was Hawaii itself,” she told him. “Hawaii was lush, fertile, alive. O’Keeffe had never seen anything like it. The abundance, the intensity of color and sensation. Then she went back to New Mexico and saw a whole new beauty in its starkness. It shaped her work for decades—the rest of her life, really. Hawaii was the catalyst, that�

�s my argument. She found something new because something new had been awakened in her.”

“You want that to be true,” he said, “but you need the data. No data, no scholarship.”

“There is data.” People had written about O’Keeffe’s time in Hawaii—not many, but a few, like Jennifer Saville in her essay for the Honolulu Academy of Arts. That wasn’t the kind of data Harold Lindstrom was talking about, of course. He meant primary data, from O’Keeffe herself. Elizabeth searched her mind for an example, a painting that showed what she was trying to convey.

“Her White Bird of Paradise,” she said. “One of the Hawaii paintings. You never see it listed as one of O’Keeffe’s major pieces but it’s where she brings the two things together, petals and bones, life and death.” She strained forward, needing Harold to see what she saw. “Those white blades, the stalks in the Bird of Paradise? They’re like the antlers and bones she painted, later, after Hawaii.”

“One painting,” he said.

“I don’t need more than one. To make my point, convince you.”

Harold laughed. “Do you give your husband a hard time too?”

Elizabeth drew back, startled by his levity. He probably thought he was being clever but it was patronizing, dismissive, maybe even illegal. None of your damn business, she thought—although, in fact, she didn’t give Ben a hard time. She was careful not to. You only gave someone a hard time if you were certain they would still want you, afterward.

She thought of the way Richard had looked at her, in the Tai Chi class. Was it really just twenty-four hours ago? The whole incident— Mr. Wu’s collapse, the paramedics—seemed to belong to another life, not the life of a devoted mother and O’Keeffe specialist.

She straightened her back. Better not to respond to Harold’s remark. Keep his focus on her as a brilliant new scholar, the one he was grooming for a place at the elite table. “I’ll start with the White Bird of Paradise and show you what I mean.”

He dipped his head, conceding that much. “All right. Email me your work plan and we’ll talk again.” Then he stood, meeting over.

“I’ll do that.” Elizabeth rose too. All that effort this morning, for a ten-minute conversation.

On the other hand, she had free time she hadn’t expected.

Elizabeth shouldered her messenger bag and clattered down the two flights of stairs to the ground floor of the Humanities building. The halls were empty; 8:00 classes were already in session, and it was too early for students with 10:00 classes to be slouched against the walls with their donuts and chai lattes, waiting for the doors to reopen.

Elizabeth herself had a 1:00 class to teach, an upper-division course called Feminist Art. It was a joke, really, when she thought about Georgia’s hatred for the whole concept. But Harold had used his influence to get her the job, and she had been grateful. Doctoral candidates had to teach as part of their training, but it was rare for someone without a PhD to be allowed to teach anything other than an introductory course. The advanced class was a star in her résumé.

Feminist Art was supposed to mean art that provoked a dialogue between the viewer and the artwork, rejected the idea of art as static, and challenged patriarchal notions of what was beautiful. That was what the master syllabus said. Elizabeth planned to assign a paper on how a woman’s gaze was different from a man’s gaze. O’Keeffe, she was sure, would have said there was no difference. You saw what you saw, if you looked, which most people didn’t. Yet O’Keeffe had also said: I feel there is something unexplored about woman that only a woman can explore.

It was too easy to assume that O’Keeffe was referring to her flower paintings, the ones people insisted were genitalia. Elizabeth was certain that it was something else. She didn’t know what that something else was, and she was pretty sure that Harold Lindstrom didn’t know either. She thought of the photographs Alfred Stieglitz had taken of O’Keeffe when they were first together, the pictures that had shocked the art world. Hands, breasts, the beautiful unpretty face looking straight into the camera. The nude headless torso, with a mass of pubic hair and legs like trees.

O’Keeffe had been in her thirties when she posed for Stieglitz, not an ingenue but an accomplished painter, even if largely unknown. She hadn’t been a passive model for someone else’s vision; she had been exploring for herself. Elizabeth had studied the photos, felt Georgia’s stern unwavering gaze.

“Oops.” A girl in a denim jacket, on her way out of the building, banged her knapsack against Elizabeth’s arm. She ducked her head in a perfunctory sorry and pulled open the heavy oak door that led to the stone steps and the quad below. Elizabeth slipped behind her, into the bright morning.

Seeing the girl, who couldn’t have been more than twenty, made Elizabeth feel ancient even though, at thirty-four, she certainly wasn’t old. At thirty-four, O’Keeffe hadn’t even begun her flower paintings. She was experimenting with shape and color. And sleeping with Stieglitz, of course.

Elizabeth flushed. Why was she thinking about all that? The Georgia O’Keeffe who had held her breasts out to the camera was twenty years younger than the woman who had gone to Hawaii. A different person, whose romance with Stieglitz had nothing to do with the subject Elizabeth had chosen for her dissertation.

Her mind skittered from Stieglitz to Ben, and the fleeting outlandish fantasy of what it would be like to face Ben the way O’Keeffe had faced Stieglitz. Really, she couldn’t imagine it. Not like that, with no purpose other than to be seen. Then her thoughts shifted again, back to the moment of shocking connection in the Tai Chi studio that might or might not have been real.

Another student brushed past her, and Elizabeth realized that she had stopped walking, frozen in place on the bottom step. Embarrassed, as if her thoughts had been visible, she adjusted the strap of her messenger bag and hurried down the path that led to the library. She strode rapidly, with more purpose than she felt, her fingers scraping against the rough bark of the trees.

She rounded the corner, and there was Founder’s Lawn. Five people were arranged in a zigzag across the grass, arms raised in The White Crane Spreads its Wings. Practicing. Or maybe that wasn’t the right word. They weren’t preparing for something that would happen later. They were doing Tai Chi right now.

Elizabeth scanned the faces, heart pounding like a teenager’s. She made herself conjure a vision of Ben, Daniel, and Katie around the dinner table. It didn’t matter because Richard wasn’t there—only three young men, an older woman with cropped white hair, and the woman in the blue yoga pants.

When they finished the sequence, the woman in yoga pants ran up to her. “Want to join us?”

Elizabeth shook her head. “I can’t. I don’t know the movements well enough.” Even if she did, she couldn’t imagine displaying her body in public like that. She could see that the woman was about to insist, so she said, “Not yet. Soon. When I’ve taken a few more classes.” Then she remembered Mr. Wu. “If we have more classes. Have you heard anything?”

“It was some kind of heart thing,” the woman said. “He’ll be okay but he needs a little time to recover.” Elizabeth felt a pang. Oh, well. Then the woman continued. “Apparently Richard talked to his daughter last night. You know, the tall guy, the one who caught him when he fell? Anyway, Sifu told the daughter to tell Richard we should keep working together until he can return. Come to the dojo. Help each other.” Elizabeth stared at her, and the woman nodded encouragingly. “It’s on the website. She put a notice up.”

Elizabeth wet her lip. “So we should come on Wednesday? Do what he told Richard?” She tried not to emphasize the word Richard, but the two syllables seemed as loud as a clarion. She wanted to say it again, more evenly. Do what he told Richard. Five words, of equal weight.

“Exactly.” The woman offered a benevolent smile. “I’m Juniper, by the way.”

“Elizabeth.”

“You sure you don’t want to join us?”

“I’m sure. I’ll see you on Wednesday, though.”

>

“Beautiful,” Juniper said. “It’s the best way to help Sifu recover. You know, work together to generate positive energy.”

“Yes. Right.” She gave Juniper a quick wave, then turned and headed across the quad. She passed the library, a stone edifice with carved lions guarding the front entrance, and the small modern building next to it that was used for public lectures and faculty presentations. Beyond the library and the lecture hall was a road that led downhill, past the admissions office and three interconnected greenhouses.

Suddenly Elizabeth knew where she needed to go. The botanical garden was one of the school’s showpieces, a must-see stop on campus tours for prospective students and their families. She glanced at the visitors parking lot next to the admissions office. Empty. It was early. The botanical garden would be a good place to wander, alone.

She followed the S-shaped path to the entrance at the midpoint of the central greenhouse. A woman with spiked hair and big copper earrings was unlocking the door. She looked up when she saw Elizabeth. “I’m a bit late opening up, I know. We’re supposed to open at nine but it’s been one of those mornings.”

“Take your time. Please.”

The earrings swayed, banging against the woman’s cheeks. “I really apologize. My student intern hasn’t arrived yet, and I’m swamped. I won’t be able to help you find anything until he comes.”

“It’s fine,” Elizabeth assured her. “I’m not a botany student. I just want to meander around in a quiet place.”

Queen of the Owls

Queen of the Owls